Chicago, años ochenta

Chicago, años ochentaEn 1977 el DJ Frankie Knuckles importa a Chicago las técnicas de manipulación de cintas que utilizaban los pinchadiscos neoyorquinos de la época underground del disco. Knuckles pinchaba sus cintas manipuladas en The Warehouse, un club gay que pronto se convertiría en la meca de las fiestas del Medio Oeste americano. La música era una mezcla de disco, soul y funk en la que, gracias a las técnicas de Knuckles, unos temas se fundían con los otros dando una sensación de continuidad y de transición fluida que podía durar toda la noche. Además, Knuckles trabajaba la producción de los temas ajenos hasta que encajaban en su línea para The Warehouse: “Tenía que reconstruir los discos hasta que funcionaban para mi pista de baile. En ese momento no se estaba haciendo música de baile, así que cogía las canciones, les cambiaba el tempo y les añadía más capas de percusión”

Si se tiene en cuenta que hasta entonces la música que se escuchaba en las discotecas de Chicago salía de los Jukebox, no es de extrañar que alguien que se tomaba tan en serio el baile se convirtiera inmediatamente en una referencia innovadora. A tal punto llegó la influencia de Knuckles que se bautizó al nuevo estilo con el nombre del lugar donde pinchaba: música house.

En 1983, Ron Hardy sustituye a Knuckles como DJ residente en su nuevo club The Music Box. Las mezclas de Hardy eran mucho más directas y menos sofisticadas que las de Knuckles. Incluían elementos ajenos a la cultura gay del momento, como la electrónica europea o el sonido industrial, que atrajeron también a un público negro heterosexual. La guinda que acabó de popularizar la nueva música de baile fue la mítica falta de medida de Ron Hardy, que dormía en la cabina mientras se hacía cargo de sesiones de setenta y dos horas.

La maquina ácidaComo sucedió en Jamaica con la explosión de los soundsystems, el nacimiento de la nueva cultura del DJ en el Medio Oeste americano necesitaba de una gran cantidad de nuevas producciones para satisfacer las ansias de novedad de un público incansable. También como en Jamaica, los elementos que permitieron que un numero relativamente pequeño de músicos proporcionaran una cantidad enorme de nuevas producciones fueron la libre disposición de un fondo común de música manipulable (en este caso funk, electro y disco) y un uso experimental, además de muy intenso, de la tecnología.

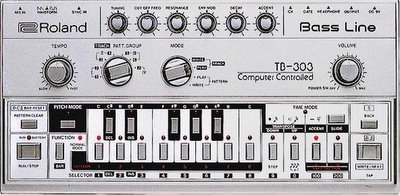

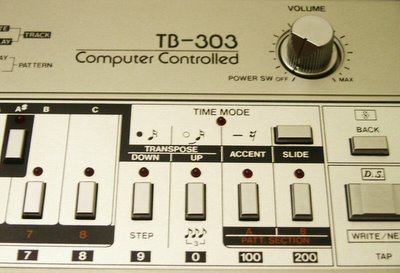

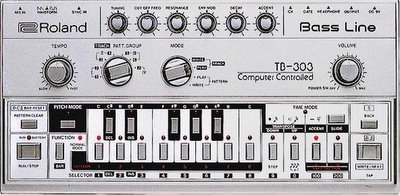

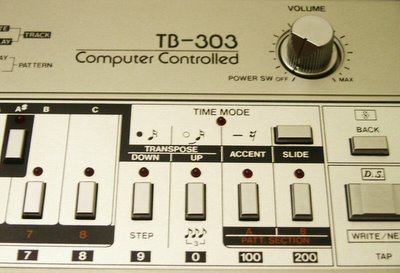

En este último capítulo es inevitable hablar de la máquina que cambió por completo el sonido de la música de baile: el Roland TB-303. Este simulador de bajo japonés fue retirado del mercado por su falta de fidelidad al sonido del bajo real y, ciertamente, el TB 303 no suena como un bajo, sino como una sirena aullante y elástica capaz de adoptar miles de matices de un mismo tono. Sin una base rítmica minimal y repetitiva como la que utilizaban los productores de Chicago, esta máquina no tiene demasiada utilidad. En cambio, para Marshall Jefferson, Phuture, DJ Skull, Larry Heard, Mike Dunn o Farley “jackmaster” Funk, las infinitas variaciones de la TB 303 fueron una fórmula perfecta para dar más contenido a las transiciones fluidas del house.

Spanky, uno de los miembros de Phuture, explica así el descubrimiento de la TB 303: “La descubrimos por pura casualidad. En aquella época intentábamos hacer algo lo suficientemente bueno como para que Ron Hardy lo pusiera en The Music Box, pero no éramos capaces: nuestras líneas de bajo no mantenían el ritmo. Hasta que una noche Pierre (la otra mitad de Phuture) me llevó a casa de un tío llamado Jasper que conseguía que las líneas de bajo se mantuvieran al mismo ritmo que la percusión usando una TB 303. Al día siguiente, después de llamar a medio Chicago encontré una en el otro extremo de la ciudad”. Poco después, Phuture sacan el primer tema de Acid House: “Acid Trax”, doce minutos de bombo y 303 chirriante que, aún hoy, sigue sonando a alucinación terminal. Según Spanky: “Lo llamé ‘acid’ porque me sonaba al viejo acid rock con un beat de fondo. […] Con ese sonido no podíamos llamarlo house porque no sonaba como el house, así que el estilo se quedó con lo de acid house”

Otro factor que promovió la explosión del acid house en Chicago, fue que estos productores se toparon con la disponibilidad inmediata de la única planta de prensado de vinilos de Chicago. Larry Sherman, propietario de la planta de prensado Musical Products, estaba fascinado con la música que pinchaba Ron Hardy en The Music Box pero no quería sacarla en su sello de blues y jazz, así que puso en marcha un sello específico para el house: Trax Records. Lo que hizo a Trax diferente de los demás sellos es que Sherman dejó el control artístico al colectivo de DJ y productores. Como cuenta el productor Marshall Jefferson: “Larry no tenía ni idea. Recuerdo que no quería sacar ‘Can U Feel It’ de Mr. Fingers [uno de los himnos del acid house]. Pensaba que era aburrido. Le dije: ‘tío tienes que sacar esto’ y me respondió ‘No lo entiendo, no tiene letra’”. Todos los grandes clásicos del acid house de esta época salieron en Trax Records.

Ácido para las masasHasta aquí la historia del nacimiento de un subgénero underground. Tanto en Chicago como en la vecina Detroit (donde se estaba fraguando el techno) las audiencias del acid house eran minoritarias y elitistas. Según el periodista musical norteamericano Simon Reynolds: “Hay una contradicción vital en la cultura house: la ideología explícita es de amor, unidad e inclusividad, en la realidad esto está limitado a los que ya están dentro, a ‘los que saben’”.

Fue en Inglaterra donde el subgénero creció hasta salir a la superficie, primero, y convertirse en un problema de orden público, después. Lo que sucedió en el Reino Unido con la llegada del acid house a los clubes londinenses (vía Ibiza) es difícil de explicar. En lo estrictamente musical, parece que hay acuerdo generalizado en que fue el house de Chicago y, más concretamente, el acid house, el estilo que impulsó la explosión de la música de baile en Inglaterra a partir de 1988. La magnitud que alcanzó el fenómeno produjo una explosión de subgéneros que eran variedades más o menos modificadas de la versión original de Chicago. Los desacuerdos surgen al analizar la cuestión desde el punto de vista político y cultural. Para algunos, la aparición de la cultura rave inglesa supone un paso más en el proyecto thatcheriano de aniquilación de la clase obrera organizada. Según esta interpretación los ravers habrían caído en la autodestrucción lumpen o en un hedonismo individualista postmoderno. Para otros, por el contrario, el auge de la cultura de baile clandestina constituye la última gran manifestación de rebeldía social de esta misma época y la sitúan a la altura política de las huelgas mineras, las protestas pacifistas contra la base de la OTAN en Greenham Common o los disturbios contra el Poll Tax.

Mientras algunos clubes intentaban recrear la atmósfera ibicenca, nacía otra forma de difusión de la música: las warehouse parties o raves en las que se ocupaba un edificio (normalmente fábricas y almacenes abandonados) para hacer fiestas de una noche. La idea inicial de estas raves era pasar por alto las estrictas leyes inglesas de venta de alcohol, sin embargo, el escaso coste relativo de estas fiestas y el hecho de que fueran públicas y, en la gran mayoría de los casos, gratuitas o sin ánimo de lucro, hizo que se generalizaran muy rápidamente hasta desembocar en el “verano del amor” de 1988. A finales de este mismo verano los medios ingleses comienzan a hablar negativamente del tema por su asociación con el consumo de drogas. En un caso típico de contrapublicidad, se produjo una escalada de las fiestas ilegales y en 1989 el gobierno endurece las medidas contra las raves promulgando una ley (que se conocería como “ley del acid house”), con la que se intentaba obligar a celebrar las fiestas en clubes legales.

Smiley contra Scotland YardAunque las medidas del gobierno habían hecho necesaria una mayor capacidad organizativa para montar una fiesta ilegal, a partir de 1991 se produjo una segunda oleada de raves que llegó de la mano de los travellers, un colectivo nómada que viajaba por todo el Reino Unido haciendo festivales en tierras ocupadas y que ya había provocado una respuesta represiva del gobierno en los disturbios de Beanfield de 1985.

La alianza de travellers y ravers produjo las mayores fiestas ilegales que se hayan visto jamás en ningún país. En esta segunda oleada de raves el elemento de confrontación política y la reflexión sobre el significado de las fiestas ilegales era mucho más visible que en el summer of love de 1988. Como decía un panfleto de la época refiriéndose al término free parties, “libres de las restricciones de los clubes que te roban, de los pubs de mierda, de los subnormales de seguridad y de los promotores enloquecidos por el dinero”. Algunos colectivos como Spiral Tribe estaban especializados en organizar fiestas interminables en lugares particularmente prohibidos por las autoridades, por ejemplo, se atrevieron con la ocupación de los mismos terrenos donde se habían producido en 1985 los disturbios de Beanfield.

La culminación de este periodo se produjo con la rave de Castlemorton Common en mayo de 1992. A esta fiesta, que duró una semana, acudieron 40.000 personas. En el período que siguió a Castlemorton se sucedieron las intervenciones de la policía, en algunos casos ultraviolentas, contra las fiestas ilegales y sus organizadores, especialmente contra Spiral Tribe. A finales de 1992 apareció la Criminal Justice Bill que castigaba con mucha dureza las fiestas ilegales y utilizaba los términos rave y “música repetitiva”.

Text by: Isidro López (LDNM)

www.ladinamo.org

Bassline BaselineVideo: history of tb303

Bassline BaselineVideo: history of tb303Documental acerca del famoso sintetizador de bajos TB 303 fabricado por Roland. (English)

Documentary by: Nate Harrison

www.nkhstudio.com

1982-1987. Tadao Kikumoto y el Roland TB-303Esta pequeña maquinita plateada (en realidad es de vulgar plástico), poco mayor que una cinta de vídeo, es la directa responsable de toda una revolución. Si la edad de oro de la música electrónica reciente empieza a finales de los ochenta con la explosión del “Acid House” (aquel movimiento que surgido de la nada llenó todos los clubs del mundo de caritas sonrientes), la culpa fue de esta belleza, la “máquina de bajos” Roland TB-303.

La historia de la 303, como la de muchos sintetizadores clásicos, está llena de circunstancias fortuitas e inesperados giros del destino. Su diseñador, Tadao Kikumoto (inventor también de la 909 y uno de los actuales capos de Roland), pensó en idear un par de máquinas que pudiesen sustituir a un bajista y un batería con el fin de que guitarristas, pianistas y orquestadores pudiesen componer sin necesidad de una sección rítmica “real”. Así nacieron en 1982 la 303 y su compañera inseparable, la caja de ritmos Drumatix 606. El concepto parecía interesante, pero fue un fracaso total. El sonido de la 303 no se parecía en absoluto al de un bajo eléctrico y programar el aparato era una pesadilla apta sólo para ingenieros aeroespaciales. Para emular los distintos tipos de bajo, la 303 contaba con unos controles circulares que había que colocar en distintas posiciones, un sistema considerado por entonces tremendamente arcaico. Sólo año y medio después de su aparición, el sinte fue retirado del mercado.

Cinco años más tarde, ya nadie se acordaba de la 303. Pero un desconocido Disc-Jockey llamado DJ Pierre encontró una en una tienda de segunda mano y empezó a utilizarla en sus actuaciones de una manera que a nadie se le había ocurrido. Efectivamente, la 303 no recordaba en absoluto a un bajo, pero si se la hacía sonar y al mismo tiempo se giraban sus controles circulares, el resultado era algo jamás oído. El impresionante chillido de la 303 impactó tanto a los productores de ‘techno’ que se convirtió en el elemento central de un sonido, el Acid House, que marcaría un antes y un después en la historia de la música electrónica.

A principios de los 90, la popularidad de la máquina ha crecido tanto que, como decía Fatboy Slim en un tema de su primer disco, “Todo el mundo quiere una 303”. El problema es que hay muy pocas: debido a su fracaso inicial, Roland sólo fabricó unas veinte mil. Despreciadas en su momento, tras el Acid los músicos electrónicos se lanzan a los mercadillos y las tiendas de segunda mano, desesperados por hacerse con una, mientras su precio en el mercado de aparatos usados sube y sube y sube... Decenas de compañías de instrumentos musicales fabricaron “clones” de la 303, pero ninguno igualaba el característico sonido de la original. La sorpresa que nadie podía esperarse, por eso, era que al final todo el mundo iba a poder tener la suya.

En 1997, la compañía de software Propellerheads lanzó al mercado Re-Birth, un programa de ordenador que emula a la perfección el clásico sonido ácido. Los músicos de todo el mundo no podían creerlo: una manera barata y cómoda de hacerse con una 303, al alcance de cualquiera. Re-Birth inaugura además la era de los instrumentos del futuro: los sintetizadores virtuales, hechos de ceros y unos en vez de transistores y circuitos.

Aunque hoy en día la fiebre por la TB-303 haya remitido un poco, el invento de Kikumoto ha ingresado en el Olimpo de los sintetizadores. Temas como “Protection” de Massive Attack, en el que sus notas se funden con pianos y secciones de cuerda, demuestran que su sonido se ha vuelto ya clásico. Pero por encima de todo, la historia de la 303 tiene una moraleja evidente. Son los creadores, no los ingenieros, los que deciden cómo debe utilizarse un instrumento electrónico.

Text by: José Luis de Vicente (Art Futura)

Quién utilizó este instrumento? / Who Played This Instrument?

2 Unlimited, 808 State, A Positive Life, Acid Junkies, Acid Rockers, Air Liquide, Alec Empire, Antiloop, Dave Angel, The Aphex Twin, John Bell (Captain Tinrib), Apoptygma Berzerk, Astral Project B.S.E., Barney Arthur, Jeff 'Skunk' Baxter, Beatmasters, The Beloved, Biochip C., Bizarre Inc, The Black Dog, Ron Boots, Cabaret Voltaire, A Certain Ratio, Coldcut, D.A.V.E., DDR, DJ Jazzy Jeff, Dreadzone, The Drummer, Eat Static, Earthbound, Ege Bam Yasi, Electribe 101, Electronic Dream Planet, FatBoy Slim, Frontline Assembly, Future Sound of London, Laurent Garnier, The Grid, A Guy Called Gerald, Groove Corporation, Haircut 100, Hardfloor, Paul Harding, Simon Harris, Richie Hawtin, HIA, Hit Squad, Human League, CJ Imperium, Lawrie Immersion, Marshall Jefferson of DJ Pierre, Guy McGaffer, Kraftwerk, KLF, KMFDM, Michael Law, LFO, Chris Liberator, Loaded, The Madness, Man Machine, Man With No Name, Massive Attack, Mega 'Lo Mania, Moby, Motiv8, Mulligan, Mushroom of Massive Attack, Nostrum, Nello, The Orb, Orbital, The Other two, Orzic Tentacles, Planet 4 Records, Ian Pooley, The Prodigy, Rhythmatic, Tom Robinson, Rowland The Bastard, Scooter, Sabres of Paradise, Kevin Saunderson, Shades of Rhythm, Insom Shalom, Shamen, Tim Simenon, Sky Cries Mary, Kris Needs, Sonic Subjunkies, Steve Smitten, Squarepusher, Switzerland, Thompson Twins Mark Tyler, Ultramarine, Ultra-Sonic, Ultraviolet, Underground Resistance, Underworld, Josh Wink

History of Chicago House Music

MUSIC IS THE KEY....

"The beat won't stop with the JM Jock. If he jacks the box and the partyrocks. The clock tick tocks and the place gets hot. So ease your mind and set yourself free. To that mystifying music they call the key". -Music Is The Key, JM Silk, 1985 House is as new as the microchip and as old as the hills. It first came to widespread attention in the summer of 1986 when a rash of records imported directly from Chicago began to dominate the playlist of Europe's most influential DJs. Within a matter of months, with virtually no support from the national radio networks, Britain's club scene voted with its feet, three house records forced their way into the top ten. Farley "Jackmaster" Funk "Love Can't Turn Around", Raze's "Jack The Groove", and Steve "Silk" Hurley "Jack Your Body", gave the club scene a new buzz-word, jacking, the term used by Chicago dancers to describe the frantic body pace of the House Sound. Whole litany of Jack Attacks beseiged the music scene. Bad Boy Bill's "Jack It All Night Long", Femme Fion's "Jack The House", Chip E's "Time To Jack", and Julian "Jumpin" Perez "Jack Me Till I Scream".

House music takes its name from an old Chicago night club called The Warehouse, where the resident DJ, Frankie Knuckles, mixed old disco classics, new Eurobeat pop and synthesised beats into a frantic high- energy amalgamation of recycled soul. Frankie is more than a DJ, he's an architect of sound, who has taken the art of mixing to new heights. Regulars at the Warehouse remember it as the most atmospheric place in Chicago, the pioneering nerve-center of a thriving dance music scene where old Philly classics by Harold Melvin, Billy Paul and The O'Jays were mixed with upfront disco hits like Martin Circus' "Disco Circus" and imported European pop music by synthesiser groups like Kraftwerk and Telex.

One of the club's regular faces was a mysterious young black teenager who styled himself on the eccentric funk star George Clinton. Calling himself Professor Funk, he would dress to shock, and stay at the Warehouse through the night, until the very last record was back in Frankie's box. Professor Funk is now a recording artist. He appears on stage dressed in the full regalaia of an old world English King singing weird acidic house records like "Work your Body" and "Visions". The Professor believes that the excitement of house music can be traced back to the creativity of The Warehouse. The Professor's memories carry a hidden truth.

The decadent beat of Chicago House, a relentless sound designed to take dancers to a new high, it has its origins in the gospel and its future in spaced out simulation(techno). In the mid 1970's, when disco was still an underground phenomeon, sin and salvation were willfully mixed together to create a sound which somehow managed to be decadent and devout. New York based disco labels, like Prelude, West End, Salsoul, and TK Disco, literally pioneered a form of orgasmic gospel, which merged the sweeping strings of Philadelphia dance music with the tortured vocals of soul singers like Loleatta Holloway. Her most famous releases, "Love Sensation" and "Hit and Run" became working models for modern house records. After an eventful career which began in Atlanta and the southren gospel belt, Loleatta joined Salsoul Records during the height of the metropolitan disco boom, before returning to her hometown of Chicago.

According to Frankie Knuckles, house is not a break with the black music of the past, but an extreme re-invention of the dance music of yesterday. He sees House music with a very clear tradition, a kind of two-way love affair with the city of New York and the sound of disco. If he were to list his favorite records, they would be a reader's guide to disco, including Colonel Abrams "Trapped", Sharon Redd's "Can You Handle It", Fat Lerry's "Act Like You Know", Positive Force "You Got The Funk" Jimmy Bo Horn "Spank", D-Train "You're The One". But most of all he relishes the sound where the church and the dancefloor are thrown together with a willful disregard for religious propriety. Religion weaves its way through the house sound in ways that would confound the disbelievers.

Most Chicago DJ's admit a debt to the underground 1970's underground club scene in New York and particulary the original disco-mixer Walter Gibbons, a white DJ who popularised the basic techniques of disco-mixing, then graduated to Salsoul Records where he turned otherwise unremarkable dance records into monumental sculptures of sound. It was Gibbons who paved the way for the disc-jockey's historical shift from the twin-decks to the production studio. But ironically, at the height of his cult popularity, he drifted away from the decadent heat of disco to become a "Born Again Christian", having created a space which was ultimately filled by subsequent DJ Producers like Jellybean Benitez, Shep Pettibone, Larry Levan, Arthur Baker, Francois Kervorkian, The Latin Rascals, and Farley "Jackmaster" Funk.

Most people believed that Walter Gibbons was a fading legend in the early history of disco, then in 1984 he resurfaced, and had a new and immediate impact on the development of Chicago House Sound. Gibbons released an independent 12" record called "Set It Off" which started to create a stir at Paradise Garage, the black gay club in New York, where Larry LeVan presided over the wheels of steel. Within weeks a "Set It Off" craze spread through the club scene, including new versions by C.Sharp, Masquerade, and answer versions like Import Number 1's "Set It Off(Party Rock)". The original record had been "mixed with love by Walter Gibbons" and was released on the Jus Born label, a tongue in cheek reference to Walter's christianity. Gibbons had set the tone again, the "Set It Off" sound was primitive House, haunting, repetitive beats ideal for mixing and extending. It immediately became an underground club anthem, finding a natural home in Chicago, where a whole generation of DJ's including Farley and Frankie Knuckles, rocked the clubs and regularly played on local radio stations.

For major house stars like Frankie Knuckles, the disco consul is a pulpit and the DJ is a high priest. The dancers are a fanatical congreation who will dance until dawn, and in some cases demand that the music goes on in an unbroken surge for over 18 hours. Mixing is a religion. Old records like First Choice's "Let No Man Put Asunder" and Candido's "Jingo" , Shirley Lites "Heat You Up(Melt You Down)", Eurobeat dance records by Depeche Mode, The Human League, BEF, Telex, and New Order, the speeches of Martin Luther King, and the sound effects of speeding express trains were all used when Frankie Knuckles controlled the decks. And the high priest of house had many desciples.

On the southside of Chicago, a young teenager called Tyree Cooper, was intrigued by Frankie's use of the speeches of Martin Luther King. He raided his mother's record collection and discovered a record by local preacher, The Rev. T.L. Barrett Jr. whose choir at the Chicago Church of Universal Awareness were the pride of the city. Tyree began using the record at local House parties and within a few months, sermon mixing, the art of splicing short gospel speeches over frantic dance music, became an established part of the Chicago DJ's art. It didn't end there.Tyree Cooper joined DJ International Records, ultimately releasing "I Fear The Night", and back home at his mother's church, the choir were beginning to excited about one of their featured vocalists

A gigantic college trained vocalist, Darryl Pandy was boasting about his new record. He had left the choir a few weeks before to sing lead vocals on Farley "Jackmaster" Funk's "Love Can't Turn Around", which against all odds was racing to the number 1 spot on British charts. House had its roots in gospel and its future mapped out. The international success of House came against all known odds. New York and Los Angeles were firmly established as the music capitals of the USA and there was virtually no room for small regional records to make a national impact. According to Keith Nunnally of JM Silk, Chicago turned their limitations into an advantage, turning the poverty of resources into a richness of musical experiment.

Despite technical drawbacks, a whole wave of new independent dance labels sprung up in Chicago. The declaration of independence was led by Rocky Jones DJ International label, a relatively small company which grew out of a DJ Record distribution pool spreading from a small warehouse near Chicago's Cabrini Green housing project, to become one of the trans- national dance scene's most influential labels. At the 1986 New Music seminar in New York, DJ International roster of artists stole the show, as every major label made frantic bids to buy a piece of the house action. Within a matter of a few days, records by the diminutive House DJ Chip E, the sophisticated gospel singer Shawn Christopher and the outrageous Daryl Pandy were sold round the world.

At the height of the bidding, JM Silk signed to RCA records for an undisclosed fortune. The commercial evidence of tracks like "Music Is The Key" and "Shadows of Your Love" proved that House music had the energy and excellence to move from being a regional cult to a modern international success. Within a matter of months every music paper in the world was praying at the feet of Chicago House. Although the first wave of interest focused on the DJ International label and particulary the unlikely duo of Farley, a legendary Chicago DJ, and his opera trained vocalist Daryl Pandy, it soon became apparent that their hit "Love Can't Turn Around" was only the peak of mid-Western iceberg. Chicago was alive with musicians. Local radio stations like WGCI and WBMX rocked to the music of the "Hot Mix 5", a group of DJ's who mixed whole nights of dance music without uttering a word and clubs like The Power Plant stayed open all-night carrying the torch once held by The Warehouse.

Locked in local competition with DJ International were a hundred other labels. The most important was Trax on North Clark Street, a label which ultimately went on to release some of house music's recognised classics. Marshall Jefferson gave Trax two of its most important records, the hectic 120 BPM "Move Your Body" and the follow up "Ride The Rhythm". His reputation was rivalled by Adonis, who released "No Way Back". The second biggest selling record Trax has ever issued, a record which reportedly sold over 120,000 copies, a staggering number for an independent record which received very little air play.

Behind the visible success story of DJ International, Underground, Trax, were countless smaller labels like Jes Say, Chicago Connectinon, Bright Star, Dance Mania, Sunset, House Records, Hot Mix 5, State Street, and Sound Pak. And behind the stars like Farley and Frankie Knuckles are numerous other musicians, like Full House, Ricky Dillard, Fingers Inc. and Farm Boy. House music has spread throughout the world. It has spread to Detroit where Transmat Records released Derrick May's Rhythim Is Rhythim record at the Metroplex Studio laying down post-Kraftwerk tracks like "Nude Photo" and "Strings".

It has spread to New York, where the respected club producer Arthur Baker has been given a new lease on life, recording unapologetic dance records like Criminal Elements "Put The Needle To The Record" and Jack E. Makossa. It has spread to London where a gang of renegade funk boys called M/A/R/R/S took the British charts by storm, climbing to Number 1 with the brillant collage record "Pump Up The Volume". It has spread into the very heart of pop music, encouraging Phil Fearon, Kissing The Pink, Beatmasters and Mel and Kim to turn the beat around. And it has infilitrated into already dynamic cultures like the Latin and Hispanic dance scene creating new possibilites for Kenny "Jammin'" Jason, Ralphi Rosario, Mario Diaz, Julian "Jumpin" Perez, Mario Reyes and Two Puerto Ricans, A Blackman, and A Dominican.

Chicago house has become everyones House. House music is a universal language. Given the undoubted international popularity of the Chicago sound, it would have been easy for the producers of House music to rest on their laurels and continually reproduce more of the same. For a while the city stuck firmly to its identifiable beat - hardcore on the one - but the experimentation which gave birth to House inevitably wanted to change it. By 1987 a new style of House music began to escape from Chicago's recording studios. It was a "deep", highly sophisticated sound, which evoked strange, almost drug-induced images.

The second generation House sound probably began with the international success of Phutures's "Acid Tracks" a hugely influential record, which captured the extreme spirit of the House scene's most ardent adherents, the hardcore dancer in Chicago, who variously experimented with LSD, acid psychedelia and new designer drugs like Ectasy. Frankie Knuckles has been careful not to sensationalise the influence of drugs. "Today there is more psychedlic sound. Acid is probably the most prevelant drug on the scene, but House is no druggier than any other scene".

None of House music's prominent performers have advocated drug abuse nor set out to glorify chemical stimulation, but an increasing number of Chicago records have controversially referred to acid tracking, the estranged synthesiser sound you can hear on several house releases. These Acid Tracks have taken house music into a new phuturism, a modern uptempo psychedelia that London club DJ's call Trance Dance. The roots of Trance Dance are not to be found in the more established traditions of 60's psychedelic rock but ironically in 1970's Europe, through highly synthesised records like Kraftwerk's "Trans Europe Express" and "Numbers".

The trance-dance sound is only beginning to establish on the Chicago Scene but it has already been adopted in British Clubs and will undoubtedly shape the new phuture of house. But beneath the abstract surface of acid-track house records is the same compulsive dance command. Frankie Knuckles is sure of that. "When people hear house rhythms they go freak out. It's an instant dance reaction. If you can't dance to House you're already dead" -Stuart Cosgrove for The History of House Sound of Chicago 12 record set on BCM records, Germany, Out of Print Inevitably, it was the restless London club scene and the illegal pirate radio stations of urban Britain that seized on the real potential of house.

The relatively cheap and do-it-yourself ethics which governed house production meant that young DJ's with inexpensive equipment could make records that were fresher and faster than the more institutionalized major labels. A series of sampled and stolen sounds, released on small scale British independent labels took the popcharts by storm, suprising the record industry and demonstrating that the house sound had a commercial appeal beyond even the wild imagination of the London club scene. In the spring of 1988 a small group of London based DJ's traded their turntables for the recording studios. Tim Simenon, working under the club pseudonym Bomb The Bass and Mark Moore using the band name S-Express had unexpected pop hits with sampled house rhythms. "Beat Dis" and "The Theme From S-Express" were charateristic of the sound that creative theft and sampling could achieve.

DJ's with huge record collections and a catalogue knowledge of breaks, beats, bits and pieces could string together an entirely new record concocted out of barely rememberal records. The masters of the London sampling scene were two unlikely DJ's, Jonathan Moore and Matt Black, who played under the name DJ Coldcut and devastated London's pirate airwaves with imaginative record choices, crazy mixes and a wilful disregard for what made musical sense.

When Coldcut's remix of Eric B and Ra-Kim rap hit "I Know You Got Soul" took the ungrateful New Yorkers to Number 1 in the pop charts in Europe it became obvious that sampling and the spirit of "Pump Up The Volume" was here to stay. The Coldcut rap mix was closely followed by the more house orientated "Doctorin The House" which featured Yazz and The Plastic People, than a cover version of Otis Clay's "The Only Way Is Up", an obscure soul sound which was big on Britain's esoteric northern soul scene. By a strange twist of history, and old Chicago soul singer from the 60's had his career momentarily revitalised by the fallout of the modern Chicago house sound.

By the summer of 1988, the British charts and teh over zealous tabloid press were over-run with acid. The music had clearly touched a raw pop nerve as one by one underground acid-house records stormed into the pop press. But their unexpected commercial success was pursued by controversy and daily press reports that the acid-house scene was a dangerous focus for drug abuse. Each new day brought increased public panic about the abuse of the synthetically compounded Ecstasy drug and by October 1988, acid house and its casual catch phrases "get on one matey", "can you feel it", and "we call it acieeeeed" were in everyday conversation.

The controversy reached its head in the autumn of press overkill when "We Call It Acieed" by D. Mob reached number 1 on the British pop charts. Radio stations were reluctant to play the record, BBC's phone in program, "daytime" had a nationwide debate on the acceptability of the song, and in a fit of moral outrage, the Burton's clothes chain withdrew smiley tee-shirts from their stores and refused to participate in the acid epidemic. Behind the hype and the press hostility the music continued its journey of unparalled progress.

If acid house had troubled the mainstream press it had also advanced the creativity of music introducing the remarkable and prodigious talent of Brooklyn's Todd Terry to the forefront of the underground dance music scene. Todd Terry is a child of house. His whole life spent buried in club culture and experimenting with the extremes of hi-tech music. Under the pseudonym Swan Lake, Martin Luther King's spiritual dream is turned into a dance floor drama, as Royal House's "Can You Party" and The Todd Terry Project "Just wanna Dance" catches the garage spirit of modern house.

-Stuart Cosgrove for The History of House Sound of Chicago The Story Continues... BCM Records, Germany Out OF Print

303 expo / Cologne / February 2006

303 expo / Cologne / February 2006welcome, acidheads!

www.303expo.com is a site about the first 303 / acid exhibition worldwide

(so far as we know...), taking place in cologne, germany, february 2006.

303 expo @ artisthotel monte christo

grosse sandkaul 24 - 26

50667 cologne - germany

let the acid take control!

www.303expo.com

In early 1981, Kakehashi was invited to rescue Brodr Jorgensen, but the scale of its debts to other manufacturers made this impossible. However, he managed to repossess the huge inventory of Roland products held by Brodr Jorgensen's liquidators, thereby stopping the world market from being flooded by cheap equipment that would have undercut Roland's own sales. Simultaneously, he was filling the hole left by his distributor's demise. Building upon the joint-venture model he had already established elsewhere, he opened four new companies in the space of just three months. Roland UK opened their doors in January 1981, as did Roland GmbH (Germany), followed in March by Roland Scandinavia and Musitronic AG in Switzerland. Remarkably, Kakehashi also found the time to establish a new Japanese division, which he opened in May 1981. Called AMDEK (Analogue Music Digital Electronics Kits) this was a conduit through which Roland would market and sell Taiwanese products to its worldwide distribution network (see the above box).So, having averted disaster, the company was able to face the future with something approaching confidence. Nonetheless, there must have been some point in 1981 when Kakehashi wondered if he had lost the magic touch. Roland and Boss launched more than 30 significant products during the course of the year yet, despite critical success, few seemed to catch the public's eye. Take, for example, the company's first big, polyphonic synthesizer and its toy bass machine. The former made little impact, while the other was soon to end up in the bargain bins, sold off cheaply for whatever dealers could get for it. But hindsight is a wonderful thing, as was Kakehashi's belief in his company and its designs. The polysynth was the Jupiter 8 (see the box on the next page). The toy was the TB303 Programmable Bass Line.Before 1981, Roland's incursions into the field of polyphonic synthesis could at best be described as 'tentative'. The Prophet 5 and Oberheim OB-series dominated, so perhaps it's not surprising that the original JP8 made little impact when it was launched. Today, of course, it's one of the most revered of all synthesizers, the icon against which all Roland's subsequent polysynths have been measured (and, for many

aficionados, found wanting...).At the far opposite end of the scale, the TB303 seemed to have few redeeming features. Initially marketed as a 'computerised bass machine', it and its stable-mate, the TR606 'Drumatix', were intended for use as replacements for a bass guitarist and drummer, tasks at which they were singularly unsuccessful. It had a single, unremarkable oscillator, a primitive envelope, and few facilities other than a built-in sequencer. Had it not been adopted for the first acid house tracks later in the '80s, it's possible that the TB303 would have been no more than a footnote in Roland's product history. And why was it used...? Largely because it was cheap and easy to understand.

Nowadays, of course, the TB303 is a staple of all types of dance music, able to chain user-programmed patterns into longer tracks, enlivened by Accent and Slide, and by the inevitable tweaks on its unusual resonant filter. Connected to a TR606 or TR808, or even the CR5000 and CR8000 CompuRhythm machines launched the same year, the TB303 produces an instantly recognisable sound that was eventually copied (with greater or lesser success) by almost every other synth manufacturer. There was even a fad in the mid-'90s for clones, with names such as MAB303, FB303, TBS303 and Tee Bee. The sincerest form of flattery indeed!

The production run of the TB303 lasted less than two years, but it's rumoured that in this time Roland churned out nearly 20,000 of them, so it's likely that they'll be with us for some time to come.

DJ Pierre aka Phuture

DJ Pierre aka PhutureDJ Pierre's real name is Nathaniel Pierre Jones and his recording names include DJ Pierre, Phuture,Phuture Phantasy Club, Pierre's Pfantasy Club, Phortune, Photon Inc. He was born in the suburbs of Chicago.

Along two other artists known as Spanky (Earl Smith Jnr –founder/technical producer) and Herb J (Herbert R Jackson Jnr - keyboards) he formed "Phuture" and together they accidentally discovered/invented the acid house noise referred to as "squelch".

Whilst trying to find out how to use the Roland TB-303 bass line synthesiser machine they had purchased they came out with the squelch sound that is the essential component for a track to be classed as Acid House. (The machine had been set at too high a pitch.) The acid squelch is a continuous stream of extremely short noise emissions played immediately after one another to effectively produce a new note tone in itself (almost like a normal tone chopped of into many smaller short notes). Note that this sound had already been used as part of other records as a sound effect. For instance you can hear this squelch sound effect used in versions of 'I Feel Love' by Giorgio Moroder and Donna Summer and 'Memorabilia' by Soft Cell. But Acid House used the squelch for the notes of the music instead of to accompany it.

The three were inspired by the new House Music revolution that had emerged from their home town Chicago's mid 1980's scene where the Hot Mix 5 artists (Farley "Jackmaster" Funk, Ralphi "The Razz" Rosario, Kenny "Jammin" Jason, Mickey "Mixin" Oliver and Scott "Smokin" Seals) were churning out hit after hit over the airwaves and tape and vinyl. Frankie Knuckles was DJing and the Warehouse club (where House Music is widely acknowledged to derive its name).

Pierre and Spanky had been to the legendary Chicago DJ Ron Hardy's club called Music Box. The first Acid House track they recorded was 'Acid Tracks' (renamed by Ron Hardy from its original title 'In Your Mind'). A slow burning, bassy, heavy, deep, unrelenting record that plays for eleven minutes and seventeen seconds.

Their first track was put on tape and first played in the Music Box in 1985 or 1986. From the overwhelming enthusiastic response from Ron Hardy (playing it several times on its first night) and the crowd, it was rerecorded at Trax Records (produced by Marshall Jefferson) and released in 1986 being the best selling house track up to that time.

From this adulation DJ Pierre went on to record a good percentage of the first Acid House tracks on Trax Records under the names Phuture, Phuture Pfantasy Club, Pierre's Pfantasy Club (with Felix Da Housecat), Phortune with notable underground hits such as Your Only Friend (Cocaine), The Creator, String Free, Got The Bug, Box Energy, Dream/Mystery and Fantasy Girl, We Are Phuture, Slam and Spank Spank.

So the Acid House style was created by DJ Pierre and co. One of the tracks has a voice proclaiming "We are The Creator of Acid Music and we're back." But apparently the term Acid was probably coined by Ron Hardy.

DJ Pierre always maintained that he was anti drugs and the track 'Your Only Friend' is most definitely has a very strong anti drugs message. Ron Hardy however was a well known party animal and drug user and perhaps the name acid was used as an LSD reference. Acid House is a very repetitive, hypnotic and trance-like music form which has a decidedly hypnotic, transcendental, psychedelic feel to it (most Acid House tracks would not have conventional lyrics on them but were either purely instrumental or only had samples/spoken rather than sung wording).

In the UK Acid House had its own dance called Trance Dance where cubbers would stand still moving one leg forward without bending the knee and back then the other leg again forward without bending the knee. At the same time hands would either be waved outstretched whilst fully extended an dmoved in a similar way to an orchestra conductor or hands would be waved around in a swirling trance like way whilst your head and eyes watched hands' motion as if transfixed or nodded in time to the conductor type movement. Often clubbers would wear tee shirts with smiley faces on them and a bandana covering the hair.

Acid House is the first true discernable offspring genre of House Music. It spawned the Rave phenomenon in the UK and the Acid House/Rave/M25 Orbital Parties including the 1988 Second Summer of Love and all its media hysteria in the UK. Very soon after came along other the House sub-genres Hip House, Detroit Techno, Deep House, Garage, Balearic then Rave but Acid was the first true one.

Later as Acid House became more and more popular and successful with clubbers and ravers it inevitably became commercial leading to many copycat tracks that jumped on the bandwagon and had Acid House remixes as well as many recordings claiming to be acid house which weren't. For example D-Mob We Call It Aceiid. This song seemed to single handedly kill the credibility of Acid House with one fell blow.

Whilst Acid House was initially a relatively short lived House trend (from 1986 in Chicago and 1987 in UK to its demise in 1989/90), it first signified the ability of House to carry on through developing, experimenting, reinventing, morphing and reacting rather than stagnating. Acid House is what kept House as a broad church alive. Chicago House was perhaps running out of steam by the late 1980s and so the quick succession from House to Acid House kept it fresh and encouraged new House genres we know to emerge and flourish. This was all created by DJ Pierre's accidental style of House and Ron Hardy's brand naming it as Acid. The rest is history. So DJ Pierre's contribution was to innovate House and protect it by allowing it to change – even if this was an accident.

Due to the notoriously unfair contracts and deals given to the innocent DJ Pierre and other Chicago House artists, none of them owned their own copyrights. None of them realised that the music they were producing was been exported and licensed overseas where in gained its first foothold in Manchester and the north of England (due to the Northern Soul movement that thrived in isolation there) before spreading at a phenomenal rate south and going pan European. Not realising how the whole Chicago House scene was infecting the world so rapidly no groundbreaking artists made money from royalties as their whole world at the time was confined the hothouse energy of Chicago itself.

DJ Pierre moved from Chicago where the House Music scene was slowing down and joined (among other labels) Strictly Rhythm records in 1990 where he was also briefly A&R manager. At this time he also went to the UK for his first visit overseas to witness how the house and acid house movement had proliferated and become so popular outside of the USA. From interviews on UK Channel 4 TV Show 'Pump Up The Volume - A History of House Music' DJ Pierre seems to be a polite, quiet, humble individual.

Other hits he released since leaving Chicago include Generate Power by Photon Inc, Follow Me by Aly Us, and The Horn Song Featuring Barbara Tucker.

He is still DJing and producing at time of writing December 2005.

Chicago's own Trax Records website says that House is "the biggest movement in club music since the dawn of Disco". But for its overall globalisation (through accompanying advances in technology affordable to youth) and its longevity, House is probably more significant than Disco. Although Disco (along with other music types such as blues, jazz ,soul, funk, rap, pop and electronica) is directly part of House's parentage. Some social observers have commented that the House movement is the biggest cultural phenomenon since Punk. But again Punk was relatively short lived from 1976 to 1980 before it became passé, compared to House that is still going strong since its birth in the mid 1980's. While punk appealed mainly to white, lower and middle classes, House's appeal is undeniably more far reaching and catholic. Twenty years after the start of Punk, the name was already a joke and meant nothing to youth of the 1990s apart from a historical event or a general term of derision – certainly not cool. House decades after its dawn is still going on and being played in clubs, on the radio and used by mainstream pop artists. Only time will tell the verdict. But DJ Pierre by creating Acid House is certainly one of the pivotal individuals responsible for spreading House's immense scope.

Text by: Dominic Higgins December 2005 (UTC)

1986 - 1989 Acid House Tracks

1986 - 1989 Acid House Tracksencuéntralos en soulseek....

www.slsknet.orgPhuture - Acid Tracks

Acid Fingers - Mix It Up

D. Mob - We Call It Acid

Armando - 151

Mr Fingers - Beyond The Clouds

Virgo & Adonis - My Space

Fingers Inc - Can You Feel It

Armando - Downfall

DJ Pierre - Acid Pop

Fingers Inc - Distant Planet

James Jackrabbit - The Last Voice

Kevin Saunderson - The Groove That Won´t Stop

Armando - Confusion Revenge

Phortune - Can You Feel The Bass

Maurice - This Is Acid (A New Dance Craze)

Phuture - Spank Spank

Mr Fingers - Acid Attack

Zsa Zsa Laboum - Something Scary

808 State - Flow Coma

Farley Jackmaster Funk - The Acid Life

Acid Over

Acid OverHouse music is so impersonal, minimal and repetitive it seems to take effect beneath the level of conscious hearing, sweeping you up by a process of `molecular agitation'. Acid house is the purest, barest distillation of house, the outer limit of its logic of inhuman functionalism. With acid, black music has never been so alien-ated from traditional notions of `blackness' (fluid, grooving, warm), never been so close to to the frigid, mechanical, supremely `white' perversion of funk perpetrated by early eighties pioneers like D.A.F. and Cabaret Voltaire.

Acid house is not so much a new thing, as a drastic, terminal culmination of two tendencies in house: the trance-inducing effects of repetion and dub production; a fascination for the pristine hygiene and metronome rhythms of German electronic dance. Pure acid tracks like Tyree's `Acid Over' recall the brute, inelastic minimalism of D.A.F. - it consists of nothing but a bass synth sequencer pulse reiterated with slight warps and eerie inflections. Other tracs parallesl the obscure innovations of bands like Suicide, the Normal (`Warm Leatherette'), Liasons Dangereuses (very big in Chicago), Die Krupps (proto-metalbashers and an early incarnation of Propaganda). Ex-Sample's `And So it Goes' combines cut-ups (`Heroin Kills'), unidentifiable bursts of distorted, sampled sound, and human cries torn from their context (agonies of ecstasy or distress), in a manner not unlike Front 242. Reese's [...]`Just Want Another Chance' sets a guttural, Cabaret Voltaire monologue of desire over the spookiest of Residents synth-drones, an ectoplasmic bassline four times too slow for the drum track. `Strings Of Life' by Rhythim-Is-Rhythim (a.k.a. Derrick May, a prime mover on the acid scene) takes the sultry swing of Latin disco and clips into a spasmodic tic that's deeply unsettling; his `Move It' is a perimeter of trebly rhythm programes that restlessly orbit the black hole where the song should be, and strangely recalls one of those lost, desolate Joy Division B-sides.

Weirdest of all is `Acid Trax' by Phuture, the record that started the whole fad off. The `Cocaine Mix' starts with a treated voice midway between a dalek and the Voice of Judgement that announces, `This is Cocaine Speaking'; spectral eddies of a disembodied human wail (reminiscent of nothing so much as PiL's `No Birds Do Sing') simulate the soul languishing in cold turkey; then we're launched on a terror-ride that again reminds me of PIL's `Careering' or `Death Disco'. `I can make you like for me/I can make you die for me/In the end/I'll be your only friend.' If disco was always ment to be about escapism, acid is about no-escapism.

In this, acid house takes after the white avant-funk of the late seventies/early eighties, its concept of disco as trance, a form of sinister control or possession. The flash and dazzle of disco classics like Chaka Khan's `I'm Every Woman', Michael Jackson's `Off the Wall' album, or anything by Earth Wind and Fire, is replaced by a clinical, ultra-focused, above all inhibited sound. Expansive and expressive gestures are replaced by a precise and rigorous set of movements, _demands_ on the body; flamboyance and improvisation by a discipline of pleasure. Perhaps there's a kind of `liberation' in submitting to the mechanics of instinct, soldering the circuitry of desire to the circuitry of the sequencer programmes.

As for the connotations of `acid', all involved in the Chicago scene deny that hallucinogenics have anything to do with the sound. The name comes from the slang term `acid burn', which means to rip somebody off, steal their ideas (i.e. sample their sound). However many club-goers take ecstasy, a drug related to LSD which provides its euphoric sense of communion (and aphrodisiac effects) without causing hallucinations.

House has been bordering on the psychedelic for some time anyway, with the spaciness of its dub effects, its despotic treatment of the voice and its interference with the normal ranking of instruments in the mix (encouraging `perceptual drift'). On one mix of Nitro Deluxe's `On a Mission', a single phrase of female voice is vivisected, varispeeded and multitraced into a sychedelic babble of sub-phonemes and vowel-particles, becomeing an airborne choir of lunatic estasied, a locust swwarm of placeless peaks and plaints spirited free of their location in a syntax of desire.

On the Kenny Jones mix of Ralphi Rosario's `You Used to Hold Me', stray sibilants from Xavier Golds's vocal flake off to bob inhumanly in their own parallel slipstream, until her vocal is absorbed into the backing track, with one spasm of passion turned into a jack-knifing rhythm effect. On the `Devil Mix' of Master C & J's `In the City', Liz Torres' voice is distored and distended in a manner uncannily akin to the The Butthole Surfers!

With pure acid house, however, it's not really a question of acid-rock's 24-track techinicolour overload, of a dazzling, prismatic opening of the doors of perception , but more like a contraction or evacuation of consciousness. Not a matter of being saturated by TOO MUCH but of being compelled to focus on TOO LITTLE, reduced to a one-track mind. If people do drop a tab or two to `acid house' they must have strage digital visions, enter Mondran phantasmagorias, Spirograph inner orbits.

What the berserk strobe-flicker of acid house is most reminiscent of is an episode from `Star Trek': miscreants are punished by bing subjected to a strobe-like flaing lightbox which clears the brain, leaving them suggestible and capable of being literally re-formed. But one deviant is left in the machine, brainwashed but unprogrammed, lost in a terrifyingly blank catatonic limbo.

Like D.A.F.'s new savagery, like psychedelia's orgiastic utopianism, house incites a superhuman/inhuman insatiability. With the jettisoning of the song/storyline, sex loses narrative and context, becomes asocial and fantastical. There's no sense of trajectory (courtship/seduction/foreplay/union), no sexual healing, no communication, no sense of `scene' in Baudrillardian sense (dramatic relations between human agents). Instead there's an ob-scene explicitness, a a graphic depiction of a fantastical algebra of pornotopian configurations. Sex turns in to a series of quadradic equations, flesh becomes spectral. Nothing is ever resolved: house is the beat that can never satisfy or be satisfied. The stutter-beats, the costive basslines, sound neurotic: the music's a repetition complex, a symptom of some unstaunchable vacancy of being. Every bar of the music becomes an orgasm, making the idea of climax meaningless.

And where acid rock imagined utopia as a garden of pre-modern innocence, acid house is futuristic, in love with sophistication and gtechnology. Acid house imagines a James Bond/Barbarella leasure paradise of gadgetry and designer drugs. House is a kind of pleasure factory (an orgasmotron, in fact) and as Marx wrote, the factory turns human beings into mere appendages of flesh attached to machinery.

If house, acid, new beat, etc, are radical, it's a radicalism that's inseparable from their simple effectiveness, pure pleasure immediacy. Here's a pop culture based around the death of the song, minimalism, repetition, departure from the stability of the key and harmonic structure in favour of sonority and sound-in-itself. No need for interpretation, context or rhetoric, all the things that people turn to the music papers for. No delay, no mediation, but a direct interface between the music's pleasure circuitry and the listener's nervous system.

Nobody even cares who made the music, which is why the personal appearances of the `stars' are so farcical (most clubgoers continue to dance with their backs turned to the stage, while the band mimes to the record). Does this make the scene dehumanized and impersonal? You could argue, as some do, that it's a realizaionton of one interpretation of punk: not `anyone can be a star' so much as `no more stars', a deconstruction of stardom (most new beat or house `stars' are merely fronts for the producer). There's a similar kind of deconstruction to that wreaked by seventies glam: the gestures and iconography of showbiz are exaggerated amplified and disconnected untile nothing is signified but a style that can only be sustained here...There's just intensity whout pretext or context (just the music).

And this is a blank generation if ever you saw one, sucked into house's void and left adrift, prettily vacant. But if the scene is `democratic', it's with a capitalist inflection; the music is pure product, consumer-tested on the dancefloor, with an inbuilt obsolescence factor. Some tracks are monumental constructions, Brutalist zigurats you could gaze at in wonder for a lifetime. But in a club, it's compatibility rather than difference that rules, with a seamlessness that has you happy as a nodding dog.

text by: Simon Reynolds, with Paul Oldfield (1990)